Name that smell—if you can't, it could be an indicator of a problem somewhere in your brain. New research suggests that scratch-and-sniff smell tests could become an easy and cheap way to detect signs of traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative ailments. Recent research found that a diminished sense of smell predicted frontal lobe damage in 231 soldiers who had suffered blast-related injuries on the battlefield. In the Department of Defense study led by Michael Xydakis of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, subjects with low scores on a smell test were three times as likely to show evidence of frontal lobe damage during brain imaging than those whose sense of smell was normal. When the sense of smell is working properly, it acts as a matchmaker between odorant molecules in the air and memories stored in the brain. Those memories are not housed in a single place, Xydakis says, but extend across many regions. Because different smell signals have to take a variety of paths to reach their destinations, arranging their travel requires a lot of coordination. “This unique feature makes an individual's ability to describe and verbally name an odor extremely challenging and cognitively demanding,” he says. A damaged sense of smell, therefore, can indicate that the ability to make those connections has been hampered by disease, a lack of sleep or, as shown in Xydakis's study, injury to the brain. The new results add to a growing understanding of the link between brain damage and an impaired sense of smell. Researchers have been working for years to use olfaction tests to track damage to the brain caused by neurodegenerative ailments such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. Kim Good, an associate professor in the psychiatry department at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, is currently recruiting subjects for a cohort study that aims to better understand the link between olfaction and Parkinson's, which could improve early identification and intervention. “Olfactory deficits are as common as tremor in Parkinson's, and they help rule out other competing diagnoses,” Good says. Smell is also the first sense to be affected by Alzheimer's, with the hallmark protein tangles of the disease appearing early in the olfactory bulb, says psychiatrist Davangere Devanand of Columbia University. Last January he and his colleagues reported the results of a four-year-long cohort study in Manhattan, which found that scores on a multiple-choice scratch-and-sniff test in which participants had to identify 40 scents were good predictors of cognitive decline. It's not hard to imagine such exams becoming a routine part of primary care for older patients. “The beauty of olfaction,” Good points out, “is that testing is easy and can be done in the family physician's office.” — Ian Chant Why Smell Is Special The unique characteristics of our sense of smell make sniff tests ideal for diagnosing brain injury. Here are some of the most interesting scientific findings about this unusual sense: —Victoria Stern Ian Chant Recent Articles Forgetting Is Harder for Older Brains Could a Neural Implant Correct Errant Thoughts? How to Intentionally Forget a Memory Victoria Stern Recent Articles Mass Shootings Are Contagious Three Books Explore the Inner World of Animals Three Books Explore the Spiral of Shame ADVERTISEMENT The adult brain can generate new neurons in the olfactory bulb, the brain region that processes smells. This area is one of just a few regions that continue to grow new neurons during adulthood. Individuals vary in how they perceive odors and whether or not they can detect certain scents, and yet humans seem to universally enjoy the smell of vanilla. Anosmia, a condition in which people completely lose their sense of smell, can be debilitating. Sufferers often report feeling disconnected from their surroundings, and many become severely depressed. Romantic couples can unconsciously sense their partner's emotional state from their sweat—and the longer they have lived together, the better they are at it. Babies locate their mother's nipples in part by learning a smell map of the breasts.

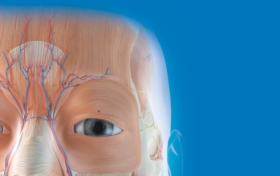

Memory for odors is particularly

complex, making scratch-n-sniff

tests an early indicator of damage

to the brain

Name that smell—if you can't, it

could be an indicator of a

problem somewhere in your

brain. New research suggests that

scratch-and-sniff smell tests could

become an easy and cheap way to

detect signs of traumatic brain

injury and neurodegenerative

ailments.

Recent research found that a

diminished sense of smell

predicted frontal lobe damage in

231 soldiers who had suffered

blast-related injuries on the

battlefield. In the Department of

Defense study led by Michael

Xydakis of the Uniformed Services

University of the Health Sciences,

subjects with low scores on a smell

test were three times as likely to

show evidence of frontal lobe

damage during brain imaging

than those whose sense of smell

was normal.

When the sense of smell is

working properly, it acts as a

matchmaker between odorant

molecules in the air and memories

stored in the brain. Those

memories are not housed in a

single place, Xydakis says, but

extend across many regions.

Because different smell signals

have to take a variety of paths to

reach their destinations,

arranging their travel requires a

lot of coordination. “This unique

feature makes an individual's

ability to describe and verbally

name an odor extremely

challenging and cognitively

demanding,” he says.

A damaged sense of smell,

therefore, can indicate that the

ability to make those connections

has been hampered by disease, a

lack of sleep or, as shown in

Xydakis's study, injury to the

brain. The new results add to a

growing understanding of the link

between brain damage and an

impaired sense of smell.

Researchers have been working

for years to use olfaction tests to

track damage to the brain caused

by neurodegenerative ailments

such as Parkinson's and

Alzheimer's diseases.

Kim Good, an associate professor

in the psychiatry department at

Dalhousie University in Nova

Scotia, is currently recruiting

subjects for a cohort study that

aims to better understand the link

between olfaction and

Parkinson's, which could improve

early identification and

intervention. “Olfactory deficits

are as common as tremor in

Parkinson's, and they help rule

out other competing diagnoses,”

Good says.

Smell is also the first sense to be

affected by Alzheimer's, with the

hallmark protein tangles of the

disease appearing early in the

olfactory bulb, says psychiatrist

Davangere Devanand of Columbia

University. Last January he and

his colleagues reported the results

of a four-year-long cohort study in

Manhattan, which found that

scores on a multiple-choice

scratch-and-sniff test in which

participants had to identify 40

scents were good predictors of

cognitive decline.

It's not hard to imagine such

exams becoming a routine part of

primary care for older patients.

“The beauty of olfaction,” Good

points out, “is that testing is easy

and can be done in the family

physician's office.” — Ian Chant

Why Smell Is Special

The unique characteristics of our

sense of smell make sniff tests

ideal for diagnosing brain injury.

Here are some of the most

interesting scientific findings

about this unusual sense:

—Victoria Stern

Ian Chant

Recent Articles

Forgetting Is Harder for Older Brains

Could a Neural Implant Correct Errant

Thoughts?

How to Intentionally Forget a Memory

Victoria Stern

Recent Articles

Mass Shootings Are Contagious

Three Books Explore the Inner World of

Animals

Three Books Explore the Spiral of Shame

ADVERTISEMENT

The adult brain can generate

new neurons in the olfactory

bulb, the brain region that

processes smells. This area is

one of just a few regions that

continue to grow new neurons

during adulthood.

Individuals vary in how they

perceive odors and whether or

not they can detect certain

scents, and yet humans seem to

universally enjoy the smell of

vanilla.

Anosmia, a condition in which

people completely lose their

sense of smell, can be

debilitating. Sufferers often

report feeling disconnected

from their surroundings, and

many become severely

depressed.

Romantic couples can

unconsciously sense their

partner's emotional state from

their sweat—and the longer

they have lived together, the

better they are at it.

Babies locate their mother's

nipples in part by learning a

smell map of the breasts.

complex, making scratch-n-sniff

tests an early indicator of damage

to the brain

Name that smell—if you can't, it

could be an indicator of a

problem somewhere in your

brain. New research suggests that

scratch-and-sniff smell tests could

become an easy and cheap way to

detect signs of traumatic brain

injury and neurodegenerative

ailments.

Recent research found that a

diminished sense of smell

predicted frontal lobe damage in

231 soldiers who had suffered

blast-related injuries on the

battlefield. In the Department of

Defense study led by Michael

Xydakis of the Uniformed Services

University of the Health Sciences,

subjects with low scores on a smell

test were three times as likely to

show evidence of frontal lobe

damage during brain imaging

than those whose sense of smell

was normal.

When the sense of smell is

working properly, it acts as a

matchmaker between odorant

molecules in the air and memories

stored in the brain. Those

memories are not housed in a

single place, Xydakis says, but

extend across many regions.

Because different smell signals

have to take a variety of paths to

reach their destinations,

arranging their travel requires a

lot of coordination. “This unique

feature makes an individual's

ability to describe and verbally

name an odor extremely

challenging and cognitively

demanding,” he says.

A damaged sense of smell,

therefore, can indicate that the

ability to make those connections

has been hampered by disease, a

lack of sleep or, as shown in

Xydakis's study, injury to the

brain. The new results add to a

growing understanding of the link

between brain damage and an

impaired sense of smell.

Researchers have been working

for years to use olfaction tests to

track damage to the brain caused

by neurodegenerative ailments

such as Parkinson's and

Alzheimer's diseases.

Kim Good, an associate professor

in the psychiatry department at

Dalhousie University in Nova

Scotia, is currently recruiting

subjects for a cohort study that

aims to better understand the link

between olfaction and

Parkinson's, which could improve

early identification and

intervention. “Olfactory deficits

are as common as tremor in

Parkinson's, and they help rule

out other competing diagnoses,”

Good says.

Smell is also the first sense to be

affected by Alzheimer's, with the

hallmark protein tangles of the

disease appearing early in the

olfactory bulb, says psychiatrist

Davangere Devanand of Columbia

University. Last January he and

his colleagues reported the results

of a four-year-long cohort study in

Manhattan, which found that

scores on a multiple-choice

scratch-and-sniff test in which

participants had to identify 40

scents were good predictors of

cognitive decline.

It's not hard to imagine such

exams becoming a routine part of

primary care for older patients.

“The beauty of olfaction,” Good

points out, “is that testing is easy

and can be done in the family

physician's office.” — Ian Chant

Why Smell Is Special

The unique characteristics of our

sense of smell make sniff tests

ideal for diagnosing brain injury.

Here are some of the most

interesting scientific findings

about this unusual sense:

—Victoria Stern

Ian Chant

Recent Articles

Forgetting Is Harder for Older Brains

Could a Neural Implant Correct Errant

Thoughts?

How to Intentionally Forget a Memory

Victoria Stern

Recent Articles

Mass Shootings Are Contagious

Three Books Explore the Inner World of

Animals

Three Books Explore the Spiral of Shame

ADVERTISEMENT

The adult brain can generate

new neurons in the olfactory

bulb, the brain region that

processes smells. This area is

one of just a few regions that

continue to grow new neurons

during adulthood.

Individuals vary in how they

perceive odors and whether or

not they can detect certain

scents, and yet humans seem to

universally enjoy the smell of

vanilla.

Anosmia, a condition in which

people completely lose their

sense of smell, can be

debilitating. Sufferers often

report feeling disconnected

from their surroundings, and

many become severely

depressed.

Romantic couples can

unconsciously sense their

partner's emotional state from

their sweat—and the longer

they have lived together, the

better they are at it.

Babies locate their mother's

nipples in part by learning a

smell map of the breasts.

Comments

Post a Comment